Older Male (30s)

Jean-Francois from Writing With Our Feet

Jean-Francois is an agoraphobic and lives in his garage, where he writes poetry with his feet. After the death of his parents, his beloved sister Sophie had taken care of him but now she is gone, too. JF must somehow summon the courage to leave his foot garage - the place where he and Sophie learned to write with their feet, in preparation for that terrible day when they might lose the use of their hands.

JEAN-FRANCOIS:

"My sister, she's dead now, she's just - gone now - that's another story and one that make less sense than anything else I could tell you. It always falls to the living to create meaning out of what's gone before… For me, it's always come from Sophie the reductivist, out here in this garage, from her feet…

She'd finish a work, shoot out of the garage and off our property. She scattered her writings about Montreal, pinning them to trees, taping them to stop signs… Her most famous ones were the God/Agog series. The entire message was God/Agog, but there were variations: God/Gagged. God/Gone. Good/God. Sophie pasted these to churches and the Gazette ran a picture once of a sexton scraping God/Agog off the front door of Christ Church Cathedral.

Mostly she worked at the bus and plane terminals. She knew that this was where her words had their greatest effect, their maximum exposure short of publication, which she opposed on environmental grounds. People would come to the bus terminal, or Dorval; they'd see her motifs and, because they were so brief, they'd carry them in their minds to wherever they were headed - to every corner of the province or any city of the world. Sophie's tiny potent foot creations. Circling the planet. Her reductivist ideology, everywhere.

This then is the comfort I derive. My sister has died without losing the use of her hands. You can over-prepare. Me, I still sit here and write with my feet because, Sophie having escaped that fate, the odds are higher now I'll lose mine. And I'm shortening up. As soon as I get to a manageable length I'll rejuvenate that chain of words my sister began. I'll leave here. I will. Of course I will…"

(Page 14)

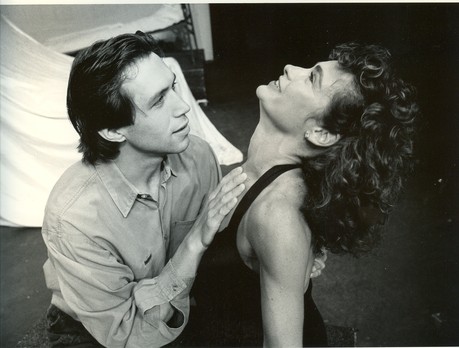

Kevin Black and Debra Gordon in Writing with our Feet (Carnegie-Mellon Showcase of Plays, Pittsburgh)

Gerald Harvie from Taking Liberties

Gerald Harvie is a young father. He has recently set up an accounting practice in Ashburnham, a small Ontario city. The era is the 1950s and a good job, with a wife and child on the way, in a postcard perfect town - it should be a wonderful life. It's not. Gerald Harvie is homosexual. And some nights, when he works late, the temptation to step outside the boundaries of "acceptable behaviour" grows too much.

At the start of this monologue, Gerald has been walking through the downtown. It's late. He is trying to turn homeward.

GERALD:

"The sidewalks pull me along. Pull me east. Pull me east, away from Claire, pull me to the park. To the park, dark breath of green; exhaling slow and clear and dark, sound receding, sounds of city sliding off behind the trees. Twisted path. Curve. Curve and dip. Duck for branch. I walk in darkness. Down through the ravine. Up through the ravine. Knowing each dipping branch, each blocking log, knowing, knowing all these things and letting myself be pulled along.

Branch brushes face. Scratch. Blood? How do I explain blood? Blood on my handkerchief. Then: ground hard as I cross the green, soft again as I slip into the trees.

Dirt breathing out. Exhaling. Carcass of rotting animal. Thread of smoke. Tobacco smoke.

Snap of twig. Fallen leaves. Leaf rustle. Rustle. Squirrel? Rat?

Glow of cigarette. Then dark. Then glow. A shape. I come close. No. No. No. I back away.

Freedom: to belong, to exist.

Strength: to be a husband, a father. To leave here. To turn away, turn home, walk home to my Claire, walk west to my Claire, to shut her reddened eyes with kisses, to walk home to her. Yes. Yes. I can do it.

No.

I turn downtown again.

There is another place. There is something I need and something I want and I know where it is.

Smell of bus, lingering smells of bus and crowds; people leaving town, good people leaving town, good people returning, destinations announced, good people greeted, people ignored, names called out, people walking through crowds unnoticed and now me, my steps ringing across deserted pavement, almost no one here now. Almost no one here.

I'm inside. There's a door. I open it and I walk down the stairs. I walk down the stairs until I reach the bottom and now there are two more doors. I am drawn to one and I go inside.

God forgive me.

I am here now. Are you there?

I have crept into the bowels of my city. I have crept here and now I stand and pretend and hope. I catch his gaze, then I look away. I look back, look away, look back and now I am no longer even in my body. I have fled that prison and I am flying a thousand, a hundred thousand miles above this green and pleasant town. I am looking back at myself walking over to my fellow human and I'm only feeling this incredible freedom and this great overwhelming rush of liberty and, finally, finally: power."

(Pp. 37-38)

The complete text of Taking Liberties

Wesley Marshall from Midnight Madness

Wesley is 32 and, since leaving high school, he has worked at Bloom's Furniture, in the bed department. Ironically, although he sells the venues for other people's sexual happiness, he has stayed resolutely alone. But now Bloom's - an old style furniture store on Ashburnham's main street - is about to close. They are having a Midnight Madness sale to clear out their remaining stock and, just as Wesley is about to close, in walks Anna Bregner, a high school classmate. Initially they get along but then they quarrel and Anna storms out, hurling insults at Wesley. She returns to apologize but Wesley is still hurt.

WESLEY:

"You stormed out of here and never let me finish what I was trying to say. We were having a good time and then whammo, out you go, and I'm all alone (Clicks fingers.) Just like that, I'm alone. You have any idea what that's like? (Pause.) No - no you don't, you don't have a clue. It's easy for you to run out of here - you've got someplace to run to. You've got people, your Mom, Jason…

What have I got? Nothing. No one. No one. No-one. When there's a symphony night I buy two tickets. I show up at the high school, they hand me my tickets and I shrug and say, "My friend's sick, I only need the one." So they won't know. I've only got one pillow on my bed - why would I ever expect a guest head? Some nights I lie there and look at the map I've got up on the wall beside my bed. I count all the dots that are cities strung out along this lonely land and I wonder, "How many Wesleys are there in this goddamn country? How many others are lying there, alone, wondering what would it be like to have a real human being breathing beside them…

In the winter I don't shovel the walk. Why would I? The only ones using it are me, the neighbours' kids flogging chocolate bars, Jehovah's Witnesses…Winter progresses, there's just this one deepening groove, one person wide, one neat path to my door that I follow up and down, up and down, until thaw… One skinny little path…"

You don't know lonely.

(p. 29)

The complete text of Midnight Madness

Wesley Marshall from Midnight Madness

Later in that evening, Wesley becomes sufficiently comfortable with Anna that he can relive the terrible day he was forced to leave high school, forever.

WESLEY:

"They'd promised me I could join the Lions Club. All of them, they said if I did my thing at the Christmas assembly nobody would blackball me. I know, I know you're going to say, 'Why would you even want to belong to a club like that?' Well, if someone offers you acceptance you don't argue. I wanted to belong. To anything! I 'd waited seventeen, eighteen years for it - it was full steam ahead, damn the torpedoes. They said I'd knock them dead. I got my toga - it was actually a flannelette sheet I'd smuggled past Mom that morning - and I changed in the dressing room and waited at the door to the gym. The cheerleaders were doing the skit before me; I stood in line behind them - they didn't really look at me, why would they? Then they ran out and did their thing and it was my turn… Billy got up to the mike and announced me. (Pause.) When he said he'd located the madman of ancient Rome, the love god of grade thirteen Latin… I knew. It was set up. But it was too late to turn back.

Do you remember how quiet it got? It's always like that before a sacrifice. My legs were trembling so much it was like walking on sticks of Jell-O. I went over to the mike and unscrewed it. That was some feat with my hand going like this. (Indicates.) And then I started.

"The skies are painted with unnumbered sparks,

They were all fire, and every one doth shine;

But there's one in all doth hold his place.

So in the world: 'tis furnished well with men,

And men are flesh and blood…"

I've run it through my head a million times. But this is where it started. Just a few at first.

"Yet in the number I do know but one

That unassailable holds on his rank…"

They were chanting by now. I should have stopped but I don't know, maybe when I did the death part, the histrionics - maybe that would satisfy them -

"Doth not Brutus bootless kneel?

Speak hands for me!"

(Mimes being stabbed.) I was drowned out by now, even with the mike. It was coming from every corner of that gym - from the front row of the bleachers where the seniors were, right up to the rafters, way back, from the younger grades and from the ones peering in from the hall - they were all shouting, it was hate, Anna, it had to have been, and I was like a lightning rod for it; I stood there and attracted hate and, when I fell to the floor, it was like a mighty wave, a mighty wave of ridicule that washed over me, all those voices, a thousand people yelling "Weirdley". Weirdley. My label. The name I'd been called right from the first day I'd set foot in that school and the name I thought I was going to leave behind that afternoon…"

(Pp. 77-79)